Operational Excellence, the Tech Lead lever

How KPIs, SLIs, and SLOs turn uncertainty into sustainable delivery

I like your article, but you do not talk about KPIs, SLOs…

This was part of Fabián’s feedback on the first article in the Tech Lead (TL) series. And he was right. The uncomfortable question was missing: how do we know if we are doing well?

If you are a Tech Lead, you will eventually be asked for “more speed”. More features. More projects. More impact. And in parallel, you will see more incidents. More alert noise. More uncertainty. More time wasted investigating things that “should not happen”.

You can have good judgment and push for quality standards. But if you cannot measure the state of the system or its real operating cost, you are flying blind. And when you’re blind, everything turns into endless discussions: “I think it is fine”, “this has always been this way”, etc. For me, that is exactly what operational excellence prevents.

Operational excellence is the team’s ability to deliver value sustainably, without degrading user trust, without burning out the team, and without every incident resetting the counter. It is a discipline, not a project.

Different metrics, different intentions

The first step is to separate by intention. If you mix intentions, you end up with pretty dashboards and zero decisions.

KPIs

Let us start by separating concepts. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are not only business metrics. There are business KPIs — conversion, retention, revenue, adoption — and internal team KPIs (lead time, deployment frequency, incident volume, cost per request, on-call noise). Both matter. But they answer different questions.

Business KPIs show whether the organization is getting value.

Internal KPIs show the operational and human costs associated with that value.

A Tech Lead primarily operates at this second layer. Not because they ignore the business, but because their lever is making the technical system sustainable as the business grows.

SLIs or “how is the system behaving”?

A Service Level Indicator (SLI) is an observable measure of how your service behaves. Typical examples:

Availability (successful requests vs. total).

Latency (p50, p95, p99).

Error rate (by type, endpoint, or cause).

Data freshness (queues, batch jobs, replication)

Saturation (CPU, memory, connection pools, queues, rate limits).

SLIs describe reality. They do not tell you whether that reality is acceptable.

SLOs or “what does ‘good enough’ look like to users?”

A Service Level Objective (SLO) is an explicit target on an SLI over a time window. For example:

Over 30 days, 99.9% of checkout flow requests must complete successfully in under 300 milliseconds.

SLOs are a form of contract. Not legal. Operational. A statement of “this is what we guarantee as a team”. One important point: SLOs are not binary. It is not about “pass or fail”. This is where the key concept comes in: error budgets.

If your SLO is 99.9%, you are explicitly accepting that 0.1% of requests may fail or be slow in that window. That failure is allowed by design, not an accident. As long as consumption of that budget is under control, the system is “within SLO”, even if incidents occur. An incident does not automatically mean you are out of budget.

A good negotiation tool

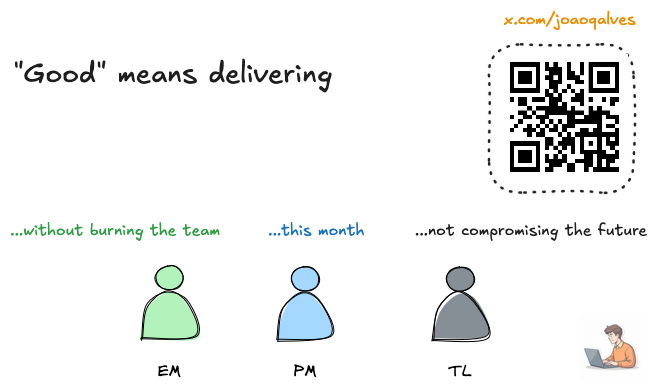

In my experience, most friction among Tech Leads (TL), Engineering Managers (EM), and Product Managers (PM) stems from the same place: a lack of a shared definition of “good”.

All three are valid. The problem is that without a mechanism, the discussion becomes political. SLOs and error budgets are part of that mechanism. If consumption is low, the team has room to take risks, ship changes, and push new features. If the error budget burns quickly, it is a clear signal to stop, stabilize, and pay down debt.

From a Tech Lead’s perspective, SLOs and error budgets are among the most powerful levers for negotiating speed, scope, and quality without relying on opinions or hierarchy.

They do not remove hard conversations, but give them structure instead.

It’s all about reducing uncertainty

Here is the key part for a Tech Lead: operational excellence is not “being an SRE” or “living in Grafana”. It is about designing an operating system for the team that minimizes uncertainty.

A TL leads operational excellence when they make it possible to:

Detect problems quickly

Diagnose with less guesswork

Mitigate in a repeatable way

Learn for real, not through incident reviews nobody executes

Keep the on-call load sustainable

Make trade-offs using data

👋 Hi, I am João. This is the third post of a series designed for Tech Leads and Engineering Managers who want to lead with greater clarity and intention.

“I’m a Tech Lead, and nobody listens to me. What should I do?”

“Operational Excellence, the Tech Lead lever” ← This article

To be continued…

I’m currently writing “The Tech Lead Handbook”, scheduled for release in H1 2026. The ideas in this series will form its core.

If you join the waitlist, you will receive a 25% launch discount.

What should they lead? What should they influence?

Clarity matters here. Otherwise, the TL tries to cover everything, becoming a bottleneck.

The TL should lead

Definition of SLIs and SLOs that represent user experience, not vanity metrics

Alerting philosophy: alert on user-visible symptoms, not internal causes

Minimum instrumentation: logs, traces, metrics, and diagnostic standards

Incident hygiene: clear runbooks, contextual alerts, and structured incident reviews

Cadence: regular review of SLOs and resulting actions

The TL should influence

Error budget policy and its impact on the roadmap, with PM and EM

Prioritization between reliability and new features, with EM and PM

Definition of technically measurable KPIs, not “wishful” ones, with PM

Investment in tooling, with EM and the relevant platform team, if applicable

The TL should not carry alone

On-call rotations and guardrails, owned by EM

External communication, roadmap decisions, and product narrative, owned by PM

Cross-org agreements and political negotiation with other stakeholders, owned by EM or PM, depending on context

The TL participates in everything. But does not own everything.

Different team archetypes, the same role

So far, I have talked about KPIs, SLIs, and SLOs in fairly abstract terms. In practice, their design depends heavily on the type of team you are in. More precisely: where is the team’s center of gravity?

Pure teams are rare. Most operate somewhere in between. Even with the Team Topologies framework, what usually changes is not the team type but its center of gravity. Some teams lean toward building and operating platforms. Others toward delivering direct product value. The framework is the same. The focus changes.

Platform teams

In platform teams — cloud infrastructure, shared components, multi-tenant services — your primary user is usually another team. That changes how you define “good”.

Let’s start with SLIs and SLOs. A globally aggregated SLI often hides real problems. You need visibility at the tenant, cluster, or logical partition level.

Support is also an explicit part of the service. Time to first response or resolution can be a perfectly valid SLO. The same applies to documentation and self-serve capabilities. They reduce tickets, interruptions, and uncertainty. They are part of reliability.

In this context, the KPIs that give a TL the most leverage are usually internal and operational:

Number of active teams or integrations

Ticket volume and deflection capacity

Unit cost per request, tenant, or key operation

Operational noise: recurring incidents, alerts, and on-call load

These KPIs do not directly measure business success. They measure whether the platform scales sustainably as the organization grows.

Common antipattern

Optimizing stability and cost without a clear signal of adoption or real value for user teams. The system works, but nobody uses it. Operational excellence without impact is also debt.

Product teams

In product teams — teams that ship and maintain user-facing features — the focus shifts to end-user experience.

Here, SLOs such as availability should not be defined at the service or endpoint level, but at the critical flow level: search, checkout, publish, book. Average latency matters little if the key funnel step is slow or failing. Correctness is also defined at the business level. An HTTP 200 is useless if the result is wrong.

This does not mean product teams lack internal KPIs. They exist and matter. From a TL perspective, two layers coexist.

On one side, internal operational KPIs:

Incident count and severity

Alert noise and on-call load

Lead time, deployment frequency, and production failures, for example, DORA metrics

Operational cost per request or per user

On the other side, product-adjacent technical signals:

Crash-free sessions.

Performance by device, version, or segment.

Functional errors that do not surface as obvious technical failures.

These internal KPIs do not replace business KPIs. But they constrain them. If the system is slow, unstable, or expensive to run, conversion, retention, and experimentation will degrade over time, even if it is not obvious at first.

Here, role boundaries matter. The PM owns the outcome. The TL ensures the system can pursue it without breaking.

Common antipattern

Optimizing conversion and experimentation while internal KPIs degrade. At first, everything looks fine. Then velocity collapses, and every change costs twice as much.

The common point

Regardless of the center of gravity, the Tech Lead’s job is the same: define what “good” means, measure it honestly, and turn those signals into decisions.

What changes is not the TL role, but where operational excellence has the biggest impact.

A simple system that works

Most teams do not fail due to a lack of metrics, but because those do not change any decisions. Not because metrics are missing, but because they do not influence real work. The key is not the tool or the level of sophistication. It is closing the loop: measure, decide, act.

In practice, teams that do this well share a pattern: few well-chosen indicators, explicit objectives, and a regular cadence to turn signals into decisions. This usually means:

A small set of SLIs that represent real system behavior

One or two SLOs per critical flow

Alerts that indicate real user-facing degradation

A clear rule for what to do when that happens

Regular reviews that turn into concrete actions

🎁 Do you want to apply this to your team?

Throughout the article, I have discussed KPIs, SLIs, and SLOs, and how to use them to make better decisions. But the difference is not understanding the concepts. It is putting them to work day to day. For that, I prepared two practical templates that I use with teams:

Define KPIs, SLIs, and SLOs, and make “good” explicit in your context.

Monthly review to turn metrics into real decisions, not dashboards.

They are not theoretical frameworks or universal recipes. They are simple artifacts to close the loop: measure, decide, act.

Subscribe and fill out the form to receive them. Free.

Note: If you already requested access to the EM/TL alignment toolkit, this is not a new download. The KPI, SLI, and SLO templates, along with the monthly review, are part of the same document you already have: the toolkit with the self-assessment semaphore that goes together with the 90-day plan for Tech Leads.

Operational excellence is how you buy velocity

Going back to what I learned at mytaxi, something simple stuck with me: being right is not very useful if you cannot move the team. And moving the team is not about explaining things better. It is about changing the frame in which decisions are made.

When you work with well-defined SLIs, SLOs, and KPIs, you stop asking for faith and arguing over gut feelings. You start operating with a system that makes trade-offs visible and decisions easier.

That is, for me, one of the biggest contributions of a Tech Lead: turning fuzzy conversations into repeatable decisions, and repeatable decisions into sustainable speed.

Because the goal was never fewer incidents for technical pride. The goal is to deliver value consistently, without burning out the team, and without living with the feeling that any Monday at 9 a.m., everything could blow up.

— João