Software in a post-abundance world

Why AI changes teams, labor, and capital at the same time

A few days ago, I wrote about how AI is making software become fast food. Code is becoming cheap, judgment is becoming the bottleneck, and value is shifting away from writing toward deciding, integrating, and operating. The reactions were interesting as many people seemed to recognize the shift without yet having a clear model for it.

Shortly after publishing it, I read another article that addressed the same issue from a different angle. Where my piece leaned more on careers and value concentration, this one stepped back and looked at industrial revolutions, disposable software, and what happens when production scales faster than stewardship.

Both texts start from the same observation. We can now generate far more software, far faster. That part is already visible. The more interesting effects appear later, once that abundance collides with markets, organizations, and incentives that were designed for scarcity.

Why did we have big teams?

For most of software’s history, large teams existed for structural reasons. Translating business complexity into working systems was expensive in terms of cognitive effort. Operating those systems reliably over time incurred additional costs. Dividing the work across people and teams was the only way to manage that load, even if it introduced coordination overhead and organizational drag.

But technical necessity is only half the story. The last decade has introduced a powerful economic incentive to rapidly expand teams. The zero-interest-rate period (ZIRP), combined with abundant venture capital (VC), rewarded speed and scale over efficiency. Hiring became a way to buy time, maintain feature parity with competitors, and signal momentum. Ultimately, hiring also became a way to preempt rivals rather than out-execute them.

Speaking with Sergi, I also agree with his take. In many companies, headcount growth was just as much about dividing cognitive load as about keeping up. If your competitor had three teams on a problem, you staffed four. That’s how roadmaps expanded, and scope creep was everywhere. Sometimes, it is because users demanded it and are driven by the fear of missing out (FOMO).

Hiring also occurred in bulk, and we observed entire teams added at once. And what happens when you do that? Exactly, talent density drops, and you end up with a myriad of processes to cope with scale. Team organization followed familiar patterns: let’s do microservices everywhere, layers of managers, and so on. What worked for a few successful companies was widely copied, often without the underlying constraints remaining the same. The result was more bureaucracy, more politics, and steadily decreasing marginal output per new hire.

None of this was irrational at the time. Capital was cheap, growth was rewarded, and efficiency could wait. The issue is that when software production becomes cheaper and faster, the justification for large teams weakens. Not all at once, and not everywhere, but enough to matter. The economic environment no longer rewards carrying excess coordination costs just to keep pace. Feature parity becomes easier to reach with fewer people, and the old incentives start to flip.

Efficiency, margins, and labor economics

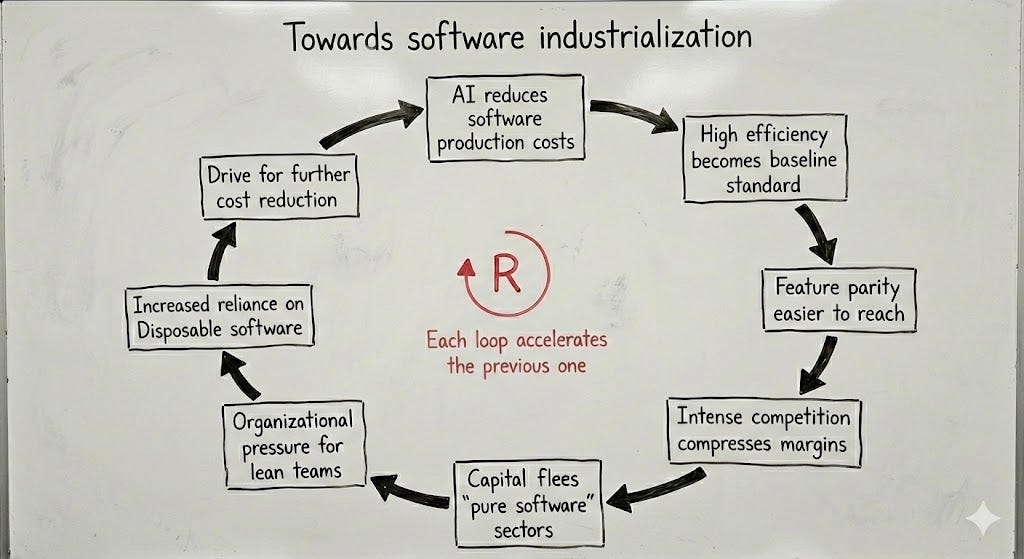

Efficiency spreads faster than culture. As more teams adopt similar AI tooling and practices, any initial advantage disappears and becomes the baseline. New competitors form faster. Existing ones reorganize. The supply of “good enough” software is growing rapidly, particularly in horizontal products and undifferentiated SaaS offerings.

This is where the shift stops being technical and starts being economic. Once feature parity becomes cheap, pricing power weakens. Margins begin to erode. Not everywhere and not uniformly, but enough to matter. Companies with strong data moats, network effects, or regulatory constraints still have defenses. Many Web 2.0 incumbents sit here. They have users, data, and distribution that newcomers cannot easily replicate.

But those advantages mainly buy time. If these companies continue to operate with cost structures, team sizes, and incentive models designed for a world in which software was expensive to produce, they become vulnerable from within. Disruption rarely comes from rebuilding the same product slightly better. It stems from a different operating model: fewer people, tighter feedback loops, less coordination, and greater tolerance for disposable output.

As margins compress, the effects cascade: we’ll see smaller teams become the norm, training pipelines shorten, and fewer hiring risks. If roles become easier to substitute, then compensation follows. Deep expertise still matters, especially where failure is costly, but the long tail becomes less differentiated. This is not a sudden collapse. It is a gradual pressure that accumulates quarter after quarter.

At the same time, owning larger domains introduces a different cost that is easy to underestimate. With fewer teams covering broader systems, the blast radius of mistakes increases. Operational risk, security concerns, and regulatory requirements drive organizations toward stronger internal platforms, guardrails, and governance frameworks. Coordination does not disappear, but gets transformed into a more centralized and formalized form.

The system ends up leaner in headcount, but heavier in constraints. This is the second-order pattern that keeps repeating: cheaper software enables nimbler teams → nimbler teams increase competition → competition compresses margins → compressed margins reshape labor economics and organizational design. None of these steps is dramatic in itself. Together, they change the industry’s equilibrium.

On disposable software

Disposable software is not merely a technical choice but also a financial one. There are growing classes of software where low expectations of longevity make sense. Internal tools, experiments, one-off agents, and workflow automations often exist to be replaced. In those cases, lower production costs change the calculus in a positive way.

Other systems do not benefit from that treatment. Software that touches money, identity, safety, or compliance accumulates risk over time. Maintenance, ownership, and long-term understanding remain critical, regardless of how cheap the initial code was to produce.

As output increases, responsibility becomes more diffuse. Dependency chains grow. Maintenance costs remain hidden until they manifest as incidents. Technical debt behaves less like a backlog item and more like an environmental problem, building quietly and affecting everything downstream.

Where the next disruption comes from

I think the next disruption won’t come from software engineers working in isolation or from incumbents slowly layering AI onto existing processes. It will arise from close partnerships between software engineers and subject-matter experts. People who understand the incentives, constraints, and pathologies of an industry and can redesign workflows from first principles.

Law is a good example. Many law firms still operate on a billable-hours model that rewards inefficiency. Partner structures, risk aversion, and legacy processes make meaningful change from within difficult. A strong engineer, paired with a lawyer who deeply understands how legal work actually occurs, can reimagine the system end-to-end. Not just automate documents, but change how value is delivered, priced, and operated.

The same pattern applies elsewhere, including accounting, insurance, and healthcare administration. Compliance-heavy industries where software was never the primary bottleneck, but where it also couldn’t realistically attack the core of the work.

That constraint is changing. It is not just large language models. It is AI-first systems more broadly: agents, retrieval pipelines, long-running workflows, and systems that can observe, reason, act, and iterate. Together, they enable work across millions of documents, contracts, emails, and records in ways that were previously impractical. They are good at mapping unstructured human input into structured systems, coordinating multi-step processes, and encoding domain logic directly into operational flows.

In Law, this means navigating case histories, contracts, and precedents at a scale no junior team could. In accounting and insurance, it means translating messy reality into systems of record with far less manual glue and back-and-forth.

The incentives were broken before. Now the tooling is finally strong enough to expose how broken they are. Cheap code lowers the cost of attacking those incentives. AI-first systems reduce the cost of understanding the domain sufficiently to redesign it.

Capital flows leverage

As margins compress in pure software, capital reallocates. VCs thrive on asymmetry. When software production becomes cheap and competition intense, volume alone no longer creates outsized returns. What matters is leverage: control over scarce resources, real-world constraints, or deeply embedded workflows.

This is why investment increasingly concentrates in contexts in which AI reshapes physical or institutional systems rather than merely improving digital ones, across healthcare, manufacturing, logistics, and defense. In these domains, software does not just optimize processes. It changes cost structures, labor models, and regulatory dynamics.

In parallel, more capital is flowing into robotics, biotechnology, and other hard-tech domains, where software amplifies physical capabilities rather than replacing them. These areas absorb complexity rather than abstracting it away, which makes them harder to copy and slower to commoditize.

Pure software remains important. But its role in producing venture-scale asymmetry narrows. The winners are less likely to be the teams that generate the most code and more likely to be those that combine software, domain expertise, and operating leverage in ways that are difficult to replicate.

This capital shift reinforces everything upstream. Lower margins in software push salaries down. Lower salaries and cheaper tooling enable more entrants. More entrants increase competition. And the cycle tightens.

Final thoughts

What’s changing is not just how software is built, but what kind of behavior the system rewards.

For a long time, the industry optimized for growth under conditions of scarcity: scarce engineers, expensive production, and abundant capital. That combination justified large teams, extensive coordination, and substantial inefficiency. It worked because the environment enabled it.

That environment is fading. When software becomes cheap to produce and easier to replace, some assumptions quietly cease to hold. Team size is no longer a proxy for progress. Headcount stops being a moat. Speed alone stops being enough. Many structures that made sense under ZIRP-era economics start to feel heavy.

The pressure doesn’t show up as a single breaking point. It appears as a series of small adjustments: teams become leaner, roles become more dynamic, and hiring gets more cautious. Disposable output becomes normal in some areas, while expectations rise sharply in others. The gap between “good enough” and “critical” software widens.

At the same time, leverage shifts. Greater value is placed on who can integrate software with domain knowledge, real-world constraints, and durable operating models, rather than on who can produce the most code. That is where capital, talent, and influence start to cluster.

None of this means software becomes less important. If anything, it becomes more embedded everywhere. But it does mean the industry looks less like a gold rush and more like an economy.

The question going forward is not whether AI will accelerate software. That is already happening. The question is which parts of the system adapt their incentives quickly enough, and which ones continue to optimize for a world that no longer exists.

— João