Tech Lead antipatterns

Five ways a Tech Lead loses impact without realizing it

There is a sentence I have heard far too many times from Tech Leads (TLs). For this article, we will talk about Cristian (a fictional name):

I already raised my concerns. If they chose to ignore them, that’s on them.

Cristian probably said this in a meeting, wrote it down in a document, and explained it on Slack, with context and arguments. And still, the team, or other Staff Engineers, architects, etc., went in a different direction or did nothing.

This article is a translation of the “Antipatrones de un Tech Lead” 🇪🇸 published last week.

From the inside, this feels like frustration. From the outside, it often looks like noise. Most TLs do not end up in this situation due to neglect or poor judgment. They get there because they care, they see risks, and they feel responsible for both the system and the team. That is precisely why this situation hurts so much.

Here is a distinction that is hard to accept: saying what you think is not exercising technical leadership.

Being right, warning about risks, or having sound judgment is not enough. And when a TL feels the needle isn’t moving, they start compensating. That is where antipatterns appear. Not as obvious failures or bad intentions, but as reasonable responses to real frustration that builds up when good judgment does not move anything.

Note: at this point, the plan was to talk about five antipatterns. Then Fabián, a Tech Lead and reviewer of the tech lead series, pointed out one more. He was right. So this starts at #0. I want to thank him for reviewing the article.

#0 The one who does not exercise the role

Before the visible antipatterns, there is often another, less obvious one. Sometimes there is no friction or visible conflict. The team delivers, meetings happen, and decisions are made. That is precisely why the situation goes unnoticed for far too long.

The problem is not what happens today, but what does not happen. Nobody is looking at the system as a whole, pushing a clear technical direction, nor turning local decisions into global coherence.

This often happens when the previous TL leaves, and no one truly fills that space. Or when the most senior engineer inherited the title without redefining the role. Or during rapid growth phases, when the highest producer is promoted because “they already know the system.”

In the daily work, the TL is present but does not provide direction. They do not push principles, do not anticipate risks, and do not articulate technical decisions beyond the immediate. They neither block nor unblock. It is not that they make poor decisions. They simply do not decide.

The effect is not immediate. Each engineer starts optimizing their own area. Decisions are made locally, and judgment fragments. Then, when a structural problem appears, nobody feels responsible for owning it.

This is often confused with autonomy, but it is actually a void. The team does not depend on the TL, but it also does not grow around a shared direction. It moves forward, but without accumulating judgment or long-term speed.

#1 Opinions with no ownership

There is a very recognizable moment when this antipattern starts. Cristian keeps participating in conversations, pointing out risks and offering judgment.

Cristian starts to take refuge in a comforting idea: “I already did my part.” He shared his opinion, left a record, and warned about the risks. If the decision goes wrong, it will not be due to a lack of warning. That reasoning is understandable, but dangerous.

From that point on, Cristian stops making decisions and limits himself to issuing diagnoses. His judgment is still good, but it no longer creates movement. He is present in the conversation, but not in the outcome.

That gap between how Cristian sees himself and how he starts to be perceived often surfaces in uncomfortable conversations. Sometimes in a 1:1:

João: Hey, how do you think the team is doing lately?

Cristian: Fine. More or less the same as always. I already said what I thought about the latency issue and the new design. If they end up deciding something else…

J: Right. The issue is that, from the outside, it can feel like you have a lot of opinions, but you are not really pushing for anything specific.

C: What do you mean I’m not pushing? I’ve been warning about the risks for weeks.

J: Sure, but warning about risks isn’t the same as leading a decision. The team leaves those meetings knowing what you don’t agree with, but not knowing what you would do differently or what you are actually willing to prioritize to change it.

C: … [he looks upset]

J: I’m not saying this as a criticism. Your judgment is solid. But right now your opinion isn’t helping the team make decisions faster. If anything, it leaves them in limbo.

Over time, two things happen:

On one hand, decisions are made despite Cristian, not with Cristian. His opinion is heard, but it loses weight. On the other hand, frustration grows because he feels his judgment changes nothing

At this point, the role begins to degrade without anyone explicitly deciding to do so. By assuming his responsibility ends at giving an opinion, Cristian reduces his impact without realizing it. His judgment stops being a lever and becomes just another comment.

This is usually the first step. When having opinions stops working, the temptation is to compensate in other ways. That is where the rest of the problems start to appear.

👋 Hi, I am João. This is the fourth post of a series designed for Tech Leads and Engineering Managers who want to lead with greater clarity and intention.

“I’m a Tech Lead, and nobody listens to me. What should I do?”

“Antipatterns of a Tech Lead” ← This article

To be continued…

I’m currently writing “The Tech Lead Handbook”, scheduled for release in H1 2026. The ideas in this series will form its core.

If you join the waitlist, you will receive a 25% launch discount. More than 100 tech leads and engineering managers already joined!

#2 The TL as a bottleneck

If opinions stop working, the next step seems logical: doing. Cristian no longer limits himself to pointing out problems; he is now getting more involved, reviewing more things, and being part of more decisions. Not because he wants control, but because he wants things to go well.

At first, it works. Decisions improve, and risks decrease. Incidents go down. The team breathes. It can even look like effective leadership.

But there is a trap. More and more decisions go through Cristian. More and more context lives in his head. More and more conversations wait for his validation to move forward. Without realizing it, Cristian becomes the point through which everything must pass.

The team adapts quickly. It learns which decisions can be made independently and which cannot. It learns when it is worth waiting and when it is not. And little by little, it stops deciding at the edges.

From Cristian’s perspective, day-to-day work becomes exhausting. He is always busy. There is always something urgent or someone waiting. And still, the underlying feeling is that the system is not speeding up.

Here is the paradox: the more Cristian tries to unblock the team, the more he slows it down. The signals usually appear late:

Pull requests waiting for review “when Cristian has time”

Technical decisions were postponed because “we need to check with him”

Incidents nobody dares to close without his sign-off

When the TL becomes a bottleneck, the problem stops being technical. It becomes systemic. The team has externalized decision-making, and the organization has concentrated risk in a single person.

And the worst: Cristian is becoming indispensable. And that, far from being a strength, is a fragility. The more the team depends on him to decide and move forward, the less time Cristian has for N+1 work. Improving the system, reducing uncertainty, or creating the conditions for others to make better decisions. His calendar fills with urgencies, and the role stops scaling.

#3 Judgement lives in the TL’s head

One day, someone asks, “Are we doing things the right way?” and nobody knows how to answer without looking at Cristian. Review becomes his center of gravity. Pull requests, designs, and implementation details go through him. Not because the team is insecure, but because there is no clear reference for what “done right” means without his approval.

Cristian reviews with good intentions. He wants to maintain quality and avoid mistakes. But feedback starts to vary depending on context, timing, or how tired he is that day. Something acceptable yesterday is questioned today. What is tolerated in one service is debated in another.

The team learns quickly. There are no explicit rules. You have to wait and see what Cristian says. And here something subtle but very damaging happens: people stop thinking about the best solution and start thinking about what will pass review. They take fewer risks, propose fewer alternatives, and ask more than necessary.

The problem is not that there are standards. It is that they are not written or shared. They live in his head and only surface during review. While Cristian is around, the system works. When he is not, the team hesitates.

🎁 Does this sound familiar? It is not a coincidence

Many of these antipatterns appear when judgment is not explicit, and the team does not share a definition of “what good looks like.”

To help move out of this, I have prepared a free alignment toolkit with practical tools already used by other teams:

For Tech Leads: a self-assessment traffic light to identify where you are adding value and where you are becoming, unintentionally, a bottleneck.

For Engineering Managers: an evaluation traffic light to give feedback based on observable behaviors, not gut feelings.

For the team: an operational principles template to take judgment out of the TL’s head and stop debating the same decisions every week.

Note: If you are already subscribed and previously requested the toolkit, you will find it in the same document.

The more time Cristian spends reviewing, the less time he has to do the work that would truly help the team grow. Clarifying principles, reducing ambiguity, and building a system that works without his constant presence. Review replaces clarity.

#4 The hero

Let’s be clear: Cristian does not wake up one day wanting to be a hero. He simply starts to notice that there are situations where his presence makes a difference.

He realizes that, in the most complex problems, people usually rely on him. Those delicate decisions wait until he is around. And that is when something goes well, it often passes through his hands.

That feels good. It is confirmation that his work matters. In a role where impact is not always visible, that feeling carries more weight than it seems.

Little by little, Cristian starts leaning on it. His professional identity becomes tied to being present, to being the one who unblocks, to being the one who “saves” the situation when things get complicated. Delegating becomes uncomfortable. Not because he distrusts the team, but because it means disappearing a bit from the center of the action.

Documenting decisions gets postponed. Giving others space to lead an initiative creates a discomfort that is hard to explain. There is no clear intention to hoard anything. He is simply always there, just in case.

The system keeps working, but it starts to work around him. Meanwhile, Cristian’s role stops evolving. The next level requires the opposite. Accepting that many things work without his direct involvement, giving up the spotlight, and measuring impact differently.

This is the point where growth stalls, because all important work depends on being present. Cristian stays busy, useful, and visible, but with less and less room to redefine his role.

The problem starts with confusing impact with presence. And when that happens, the TL stops growing.

#5 Winning all the arguments while losing the team

This antipattern does not start with conflict or a heated discussion. It starts with a sense of calm. Meetings get shorter, decisions seem to flow, and conversations close quickly. Cristian presents his point of view and, most of the time, nobody challenges it. Everything can even look aligned and efficient.

Inside the team, however, something has changed. Alternatives are becoming increasingly rare, and uncomfortable questions are rarely raised. Not because they do not exist, but because the conversation’s outcome feels predictable. The team implicitly learns what is worth debating and what is not. Cristian is not aware of this change. To him, things simply work better than before. The first time he hears it framed this way is in a conversation he did not expect:

J: There’s something I’ve been thinking about for a few weeks and wanted to run by you. The team barely talks anymore, right? Meetings are very quiet.

C: And is that a bad thing? Moving fast can be a good sign too.

J: Sometimes, yes. The problem is when that calm doesn’t come from clarity, but from assuming the discussion is already over before it even starts.

[Cristian looks confused]

C: I don’t think anyone is holding back.

J: It’s not that they’re holding back. They know how the conversation is going to end. And when that happens, people stop bringing alternatives.

C: …

J: You have strong judgment, and the team respects it. But right now it feels like your point of view carries so much weight that it takes up almost all the space.

[Cristian nods slowly]

J: When a team stops thinking out loud, something gets lost. And it usually happens without anyone noticing.

The team keeps delivering, and everything appears to work. But it no longer thinks out loud. Responsibility for decisions gets diluted, and engagement becomes more superficial. Execution is good, but questioning is rare.

Winning all the arguments has a cost. When the TL becomes, even unintentionally, the only voice that matters, the role ceases to fulfill its purpose. Because technical leadership is not about always being right, but about creating the space for others to develop judgment too.

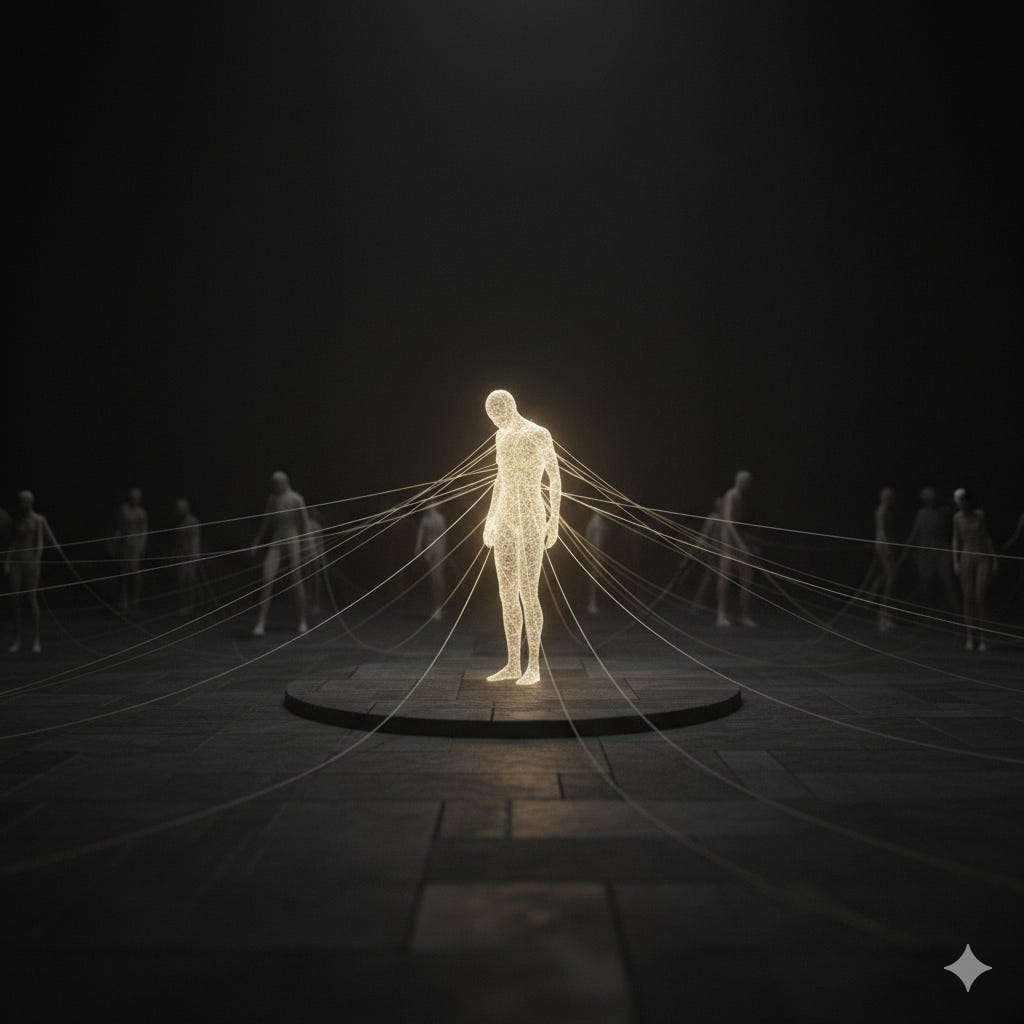

When the TL takes too much space

When rereading these antipatterns, there is a temptation to think of them as “mistakes.” They are not. Most of them, au contraire, appear because of involvement, judgment, and a real sense of responsibility when the system and the team seem to be heading toward danger.

The problem is that when a TL feels their voice does not move anything, they start compensating with behavior. They push opinions harder, get involved in everything, and review more. In short, they become indispensable and, unintentionally, take up so much space that the team stops thinking out loud.

If there is one thing that connects all these scenarios, it is this: technical leadership is not measured by how many times you were right, but by how much judgment and autonomy the team around you gains.

And here is the uncomfortable question worth asking from time to time, especially when you catch yourself saying “I already said it”: Am I helping the team depend less on me, or am I building a system that only works when I am there?

— João